Let’s begin breaking down Notre Dame’s 2019 advanced stats starting with the unit that enters the fall under the most scrutiny, the Irish running game. Since 2017’s record-setting efforts on the ground, the Irish have struggled to run efficiently, especially in big games, and been plagued by high stuff rates. What improved last season, and where can Notre Dame look for hints of promise – or is all of this hopeless without a proper fullback?

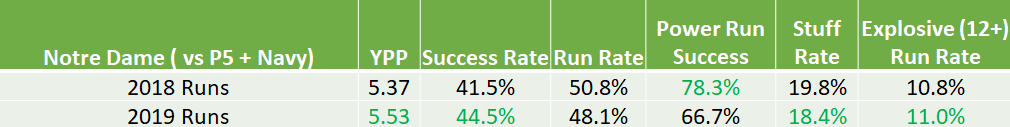

This will be the first in a multi-part series breaking down the ND rushing offense and defense, passing offense and defense, and then a high-level review that will include turnovers, special teams, and more. As usual garbage time is excluded from these numbers, and for ease in comparing 2018 vs 2019 numbers I’ve included only P5 opponents + Navy. If lost, this handy advanced stats glossary will help if needed.

A small, disappointing step forward

The Irish running attack was the single weakest part of 2018’s playoff team, finishing a dismal 72nd in Rushing S&P+ despite an explosive senior campaign from Dexter Williams. The game-breaking runs from Dex masked real issues – below average run efficiency driven by a startlingly high percentage of stuffed runs. Football Outsider’s offensive line metrics were extremely unkind to Jeff Quinn’s group, rating the unit 100th or worse in FBS in opportunity rate, line yards per carry, and stuff rate. Hiccups were expected after losing Quenton Nelson and Mike McGlinchey, but these were more like dry heaves.

With the returning continuity on the offensive line, the run game felt like a lock to improve, even with uncertainty about what back (or backs) could step in to replace Williams’ production. There was spring and fall camp excitement about two-backs sets, Jafar Armstrong’s versatility in the passing game, and the potential of Kyren Williams. And on the ground, Notre Dame did improve in key areas – but ever so slightly.

Maybe most disturbingly the run game was nonexistent in both 2019 losses. In Athens, the Irish barely even attempted to run the ball, with just 14 carries in 61 offensive plays. Against a tough Bulldog defense, the numbers were decent – near-average efficiency (42.9% run success) and 3.29 yards per carry – but Kirby Smart’s defense quickly figured out that the game would rest almost completely on Ian Book’s shoulders. Against Michigan, the entire offense was disastrous in rainy conditions, but the Wolverines averaged 5.32 yards per run versus just 1.52 for the Irish.

Big plays fueled by non-RBs

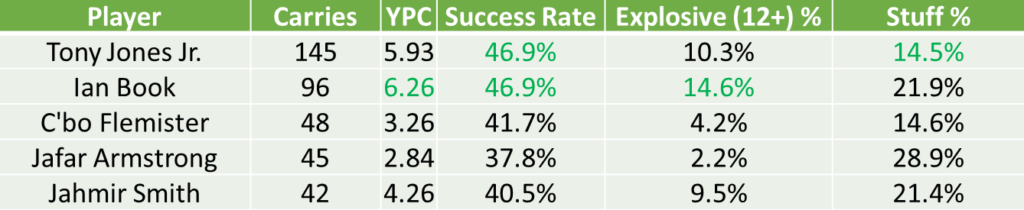

Tony Jones Jr. closed the season out on a positive note with a monstrous 84-yard touchdown against Iowa State, but for much of the season, ND running backs struggled to break explosive runs. The longest Irish run versus UGA was Ian Book for nine yards. Against Michigan? Again a nine-yard Book rush, with the long RB carry a 5-yarder by Jones. The near-loss to Virginia Tech was the same story, with a 13-yard gain by Book the long run of the game and just two 10+ yard gains by running backs in 22 carries.

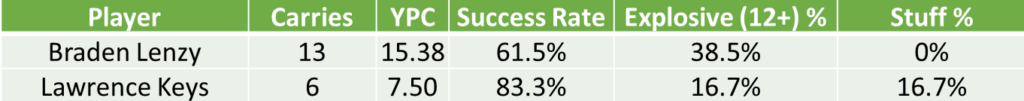

In 2018 the Irish had 18 runs of 20+ yards (excluding garbage time), with Dex accounting for half of those. The 2019 team managed to come close to replicating that production, with 15 runs of that length. But the position group distribution was far different, with 47% (7/15) coming from Book and Braden Lenzy, versus only 27% coming from non-running backs in 2018 (all by Wimbush + Book). When Ian Book is the most explosive runner of your ball carriers with 15+ carriers, it’s probably not a great sign!

The data above doesn’t portend well for the running back room next year – you’d like to see some glimpses of greater explosiveness or efficiency from Armstrong, Flemister, and Smith. The best thing in terms of optimism might be that these aren’t huge samples, run success rates will be highly tied to OL play as well as the back, and that Armstrong wasn’t right all year after his injury in the opener. You could also argue that next year’s two most talented backs are Chris Tyree and Kyren Williams and neither had enough carries to make this list.

But once you get past the lack of explosive runs from running backs, the threat of Lenzy in the run game and Book’s increased rushing production down the stretch reason are cause for 2020 optimism. Without a proven dynamic back, the threats posed by Book’s legs and Lenzy or Lawrence Keys on jet sweeps will be key.

Too much man-ball on 3rd and short?

One area where the Irish took a step back in the run game was in power run situations, 3rd/4th downs of 2 or less to gain. Notre Dame ranked 102nd in FBS in these situations and saw a major drop-off in overall 3rd down conversion rates in 3rd and short regardless of run or pass. On 3rd and 2 or less the Irish converted 78.3% in 2018, but just 58.8% in 2019.

What’s fascinating is that Notre Dame relied far more on running the ball in these situations this past season, passing on just 19% of these short 3rd downs. The previous season (when they even had a special short-yardage package early for Book) the Irish offense passed on nearly 40% of those situations and were extremely successful at it, converted 12 of 15 pass attempts into first downs! This success and lack of predictability likely helped the run game as well, as defenses couldn’t sell out for a run, and it’s strange this approach wasn’t carried through into 2019.

Is trading Chip for Tommy good for the run game?

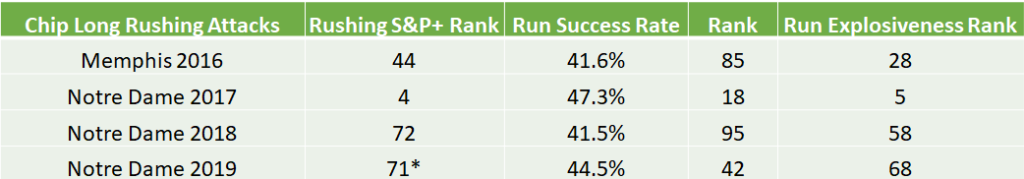

One of the worst ongoing message board debates of last season was who to blame for the inconsistencies in the run game. Recruiting misses and a talent and experience gap in personnel? Jeff Quinn and the offensive line? Chip Long and playcalling? These are all inextricably linked, and the answer is likely some combination of all of the above and that we’ll never know for sure. But we do have some insight into Long’s impact on the running game and a very limited preview of what the new play-caller might want to do.

*Since team advanced stat profiles weren’t available last year with Bill Connelly’s move to ESPN, this is using Run EPA / play via @CFBDatabase, a solid approximation but without adjustment for strength of schedule

The crown jewel on Chip Long’s resume is the 2017 rushing attack that featured Josh Adams and Brandon Wimbush rolling behind a dominant Joe Moore Award-winning offensive line. In nearly every season of Long’s playcalling career though, the rushing success rate has lagged behind explosiveness, to the point where this feels more like design than coincidence. In his sole year in Memphis the pedestrian success rates were at least paired with solid explosiveness; the last two seasons the Irish have been nondescript on the ground in both key categories.

We know very little about Tommy Rees’ vision for the offense and playcalling tendencies, but in the Camping World Bowl he did opt for runs on 18 of 26 1st downs (69%, nice). While the Irish leading for the entire game, that’s a significant increase from Long’s average 1st down run rate of 52% and easily the highest of the season (runner-up being 21 of 34 1st down runs against USC – 62%).

The run game should improve (this time we mean it)

On paper, Rees will inherit an offense that should be able to dominate in the trenches. It’s a ridiculous blend of experienced talent, with three top-100 recruits that each will be in at least their third season starting. Aaron Banks and Jarrett Patterson only figure to improve. Tommy Tremble’s blocking improved by leaps and bounds as the season wore on, and Brock Wright provides an experienced in-line option to pair with him. The Irish figure to have significant advantages versus any non-Clemson defensive line they’ll face in 2020 (only Wisconsin has much of an argument).

It’s worth noting, however, that returning offensive line starts are least correlated with strong offense the following season compared to other position groups. From Bill Connelly’s updates on returning production last year:

Returning experience on the offensive line doesn’t have nearly the statistical impact that we expect. But with more data in the bank — and a new set of tweaks to S&P+ that I’ve been unveiling at Football Study Hall — we can see there’s a little correlation.

The higher the number, the more likely returning production in these areas is to coincide with strong offense:

Receiving yards correlation: 0.324

Passing yards correlation: 0.234

Rushing yards correlation: 0.168

Offensive line starts correlation: 0.153With more data, the offensive line correlations have begun to grow stronger, which makes sense, but the conclusion remains: continuity in the passing game matters a hell of a lot, and continuity in the run game doesn’t have as strong an impact.

There’s virtually no way the running game will be worse next year, but the floor shown in 2019 underwhelmed. The offensive line’s combination of experienced depth will be unparalleled in Brian Kelly’s tenure. Jones Jr.’s all-around competence will be missed, but the potential of more dynamic rushing threats – via more Lenzy, Kyren Williams, Tyree, or a breakout by Smith – holds promise. The most pressing question will be how much the run improves under Quinn and Rees, and whether that improvement translates into something that can be effective or at least has to be respected against the schedule’s toughest defenses.

I’d like to buy a lot of Lenzy stock but it may be getting quite expensive.

It probably is, but the bigger problem is that it is really the only stock available on the running game other than Book. The rest are all essentially venture capital deals. Armstrong is a rebound stock

Plus, at the end of the day, while Lenzy running is great, you need your backs to do what they were recruited to do and get the yards. …

Sadly, it makes no sense to run a jet sweep on third and one.

How many Lenzy jet sweeps are too many? Would it be crazy to try to feed him like 4 or 5 per game? Would that be too predictable?

I liked the twists they were bringing in to start bringing him in motion, fake it, then go back the other direction with a quick pass. Some nice misdirection could open up off that.

Or better, fake the jet sweep to a motioning Lenzy, then fake the misdirection and Lenzy runs a wheel route and you go back to him with a long pass. Feel like they would have to get creative, but hey, gotta figure out a way to get him touches. Run the jet sweep a few times to keep it honest and then start getting wild. Or maybe even use him in motion as a complete decoy and have the play go an opposite direction.

Yeah I think it doesn’t always have to be jet sweeps, but ideally lots of motion whether it’s with a hand-off or touch-pass or as a decoy. Would be cool to also occasionally line him up in the backfield and give him a sprinkling of carries from RB, or motion out as a receiving threat and watch defenses freak out, in the screen game etc. The theoretical personnel grouping of something like Kyren Williams + Lenzy + Austin + Keys + Tremble could give defenses fit with the versatility of those guys as receiving and running threats.

If you figure you run about 70 plays on offense a game, give or take. Presumably, he won’t be on the field for 10 of them. Then you have to assume that some of the imes he comes in motion, he is a decoy otherwise the defense shifts outside and there is no blocking. So his decoy % would have to be about 50%, which would mean to give him 5 a game, he would be coming in motion 10 times, or 16% of the plays he is on the field. Seems like a lot. Also, you are running him sideways and his highest and best use in the passing game is running vertical. Better to get the backs doing their job.

Now, you could give some to Keys. Maybe you run 4-5 jet sweeps a game split between those two, maybe Austin and Johnson.

I think it was Tim O’Malley talking on the II podcast recently about how he doesn’t know how much Keys + Lenzy will both be on the field at the same time as they feel it might reduce their run blocking abilities on the field. Something to keep in mind, so kinda like you’re saying maybe it’s Keys and Lenzy in sort of the same role. And then either 2 TE personnel or at least one big WR (McKinley or the grad transfer from NW whose name I can’t spell yet) that will be often on the field to support the run game.

I feel like right now the fan expectation is Austin-Lenzy-Keys in slot for the base offense, but it’ll be interesting to see if that group really plays a lot together. Could be wrong but IMO Rees is going to be more of a power/run offense in 2020 behind a vet offensive line than a spread/vertical offense. I suppose we’ll see, fun to think about in February.

Yes, fun in February, I like that… this time between the Super Bowl and the start of spring ball is always so doldrum-y.

Like a lot of us, I am interested to see how much time Jafar gets in the slot.

Honestly, I’d like to buy a lot of stock in kyren Williams. I know it was a very small sample size, but he demonstrated good elusiveness (compared to our other running backs) in the 2019 spring game. Now, with a full year under his belt and in the weight room, I’d hope he can receive at least 40% of the carries next year.

If he makes that step, I believe ND’s running game as a whole will make that step as well.

I was all in on the Williams hype train last year and I am still holding on. There is basically no reason to RS running backs, especially in a year where we played so many bad ones. Makes me wonder if this was a double secret probation RS type of thing.

I wouldn’t say it was secret, he was bad in the Louisville game and basically passed over after that point. A bit odd to have such a short leash, perhaps, but I guess that shows how much faith the coaches had in him.

Signing day update: We finished #17 in 247 composite, just behind Washing, PSU, and Michigan. Stanford finished 21, USC finished 55 lolz. On Rivals we finished 20th, behind FSU woof.

This feels like one of the better classes of late, as opposed to our worst one of the BK era. I guess last year we got 16 composite 4 stars, while this year only 9 because we only had 16 total commits (excluding the long snapper). Looking back, I think this is the only class under 20 since 2012, so it is way smaller. Really could have used 2 stud CBs. Being 5 bodies

We did get our first composite 5 star since Kraemer (#27) in 16, and outside of Kraemer, Mayer (#31) and Johnson (#36) are the highest rated prospects we have signed since the incredible 2013 class.

But overall, we haven’t turned one of the strongest runs in recent memory into a huge boom on the trail (especially not in the secondary).

It won’t be remembered this way, but I would like to see the ranking by % of size of the class. That’s a better way of looking at a small class size.

On 247 our average per player was 90.75, 7th best in the country. However, I disagree that it is a better way to look at it. I think it should be taken into account when considering the class, and I think we do qualify as better than the 17-20th best class all things considered, but I definitely believe we are closer to 17 than we are to 7.

High numbers are a good thing. The more chances you have to find good players, the better. In the end, we only signed 9 4 stars. I am pretty sure the staff would have liked to sign more, especially in the secondary, where we signed zero 4 stars.

Well, I kinda respectfully am not sure I concur, in that the reason this was a small class was that we had a coupe of larger classes, not so? So maybe we need to look at two year averages? I defer to the recruiting gurus. I miss the old old days, when we would arrive for school and we would find out that some really good players had shown up for summer camp…

Our two year average isn’t better. Alabama’s 2019 class is better than our 2019+2020 classes combined (in fairness it’s almost as good as Clemson/tOSU/LSU’s 19+20 classes).

Total 5/4 stars the past 2 years

2020 – 2019 – 2 year total

Championship Level Teams

UGA: 4/15 – 5/15 – 9/30

Bama: 4/17 – 3/23 – 7/40

Clemson: 5/12 – 1/12 – 6/24

tOSU: 3/14 – 3/9 – 6/23

LSU: 3/14 – 3/11 – 6/25

Our Tier

Michigan: 0/14 – 2/14 – 2/28

Stanford: 0/6 – 0/8 – 0/14

USC: 0/2 – 0/7 – 0/9

OU: 0/14 – 3/13 – 3/27

Oregon: 3/7 – 1/11 – 4/18

Texas: 1/14 – 2/15 – 3/29

FSU: 0/8 – 0/9 – 0/17

PSU: 0/11 – 1/17 – 1/28

ND: 1/8 – 0/16 – 1/24

Teams we are out recruiting: FSU, USC, Stanford

Teams out recruiting us: Michigan, OU, Texas, PSU, Oregon

In the past two years we have had better seasons than every team in our tier except for OU, and yet ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. This is what my point really was. We’ve had our best 3 year stretch since I’ve been a fan, and our recruiting rankings are getting worse, not better.

Our recruiting is absolutely strong enough to be a 10/11 win team year in, year out, and obviously good enough to make the playoff once in a while. But if we want to beat Clemson, Bama, UGA, LSU, tOSU two weeks in a row, we need better recruiting. The playoff means that only truly elite teams will win a title, of which, we are not.

One last point. It isn’t as though our recruiting is actually getting worse relative to ND. As I mentioned, this class has the most elite talent we’ve seen since the 2013 class, and as you mentioned the per player talent is very good. I think the big difference is that other schools are recruiting even better.

We are improving in an absolute sense, but the landscape around us is improving more (other than USC HAHAHAHAHA, god bless Clay Helton, this could legitimately be their worst class of all time. 2 four stars! 2!).

Juicebox, a couple of days late, but many thanks for your thoughtful and informative replies above. Puts the whole affair in a clearer framework.

I have to think BK gets it, just based on that last foray around the bowl game, about changing his mind and thinking that it is doable to get more elite athletes. But was he just whistling in the dark, or did he have a serious conversation with Admissions…?