Wrapping up the advanced stats from Notre Dame’s regular season with an eye toward Clemson – how can the Irish move the ball on the nation’s top defense? The numbers provide strong evidence that it’s time for Ian Book to really air it out.

Irish Run Offense vs. Clemson Run Defense

Running into an orange wall

One of the biggest stories of the offseason was Clemson’s monstrous defensive line of potential 1st Round NFL picks all choosing to return for 2018. Junior Dexter Lawrence was the only one without an option to return, but Clelin Ferrell and Christian Wilkins seemed locks to last at longest until early in the second round and chose to come back to play for Dabo Swinney and Brent Venables for one more year. Austin Bryant’s stock was maybe a touch lower that the rest of the trio, but he was coming off a junior season with 15.5 TFL, 8.5 sacks, and a pick.

It’s been the rare winter storyline that has lived entirely up the hype – the Tigers were the top defense in the nation per S&P+ and 3rd in FEI. The defensive line, as expected, has fueled that dominance, leading the nation in opponent yards per rush, Rushing S&P+, opponent run explosiveness, and line yards allowed per carry on both standard and passing downs. Clemson is 3rd in run stuff rate, stopping 27% of opponent runs for no gain or a loss.

The vaunted line leads FBS in DL havoc rate, with a 10.9% havoc rate just as a unit that is more than double the national average (5.0%) and more than a handful of FBS defenses as a whole (including Louisville, who was dead last in FBS in the category – hey, Brian Van Gorder). They’ve managed to be this incredibly disruptive without giving up big plays either – the Tigers have yielded just four rushes of 30 yards or more, a top-10 figure nationally and tied with Notre Dame. Without factoring in garbage time, which was substantial in a weak ACC, only four of Clemson’s 13 opponents managed over three yards per carry, and not a single one broke four yards per rush.

An explosive yet inconsistent Irish run game

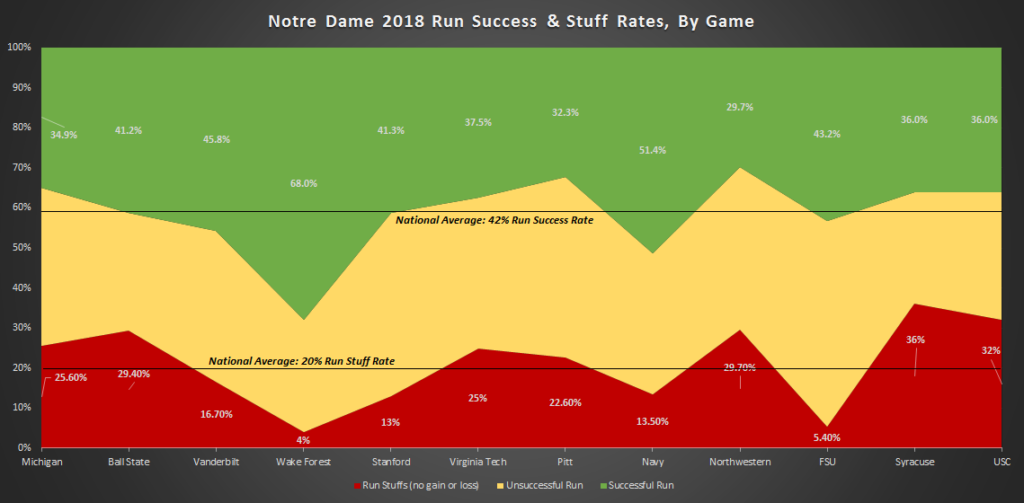

Meanwhile, the major weaknesses in Notre Dame’s profile is the run game. Following the loss of Josh Adams, Quenton Nelson, and Mike McGlinchey to the NFL (where they are all currently starting, and playing well), the running attack took a major step back to 74th in Rushing S&P+. The major cause? Inefficiency and a lack of consistent success running the ball, caused in part by excessive stuffed runs for no gain or a loss.

The Notre Dame running attack generated above-average efficiency just four times this season, in games against weaker defenses in Vanderbilt (70th in Defensive S&P+), Wake Forest (78th), Navy (120th), and Florida State (a decent 41st). For the entire season the Irish finished a ghastly 95th in marginal rushing efficiency, and you can see a bit of decline after the Stanford game when Alex Bars was lost for the season.

Not only was the efficiency poor, but those unsuccessful runs were also more damaging for Notre Dame than most teams. The Irish allowed a ton of run stuffs and tackles for a loss, especially over the second half, where three of the final four opponents had stuff rates near or above 30% (a number which is better than any FBS team this season). Some of that is scheme, sure, but if Northwestern, Syracuse, and USC are keeping you from positive yardage on around a third of your runs, what will Clemson’s front seven do?

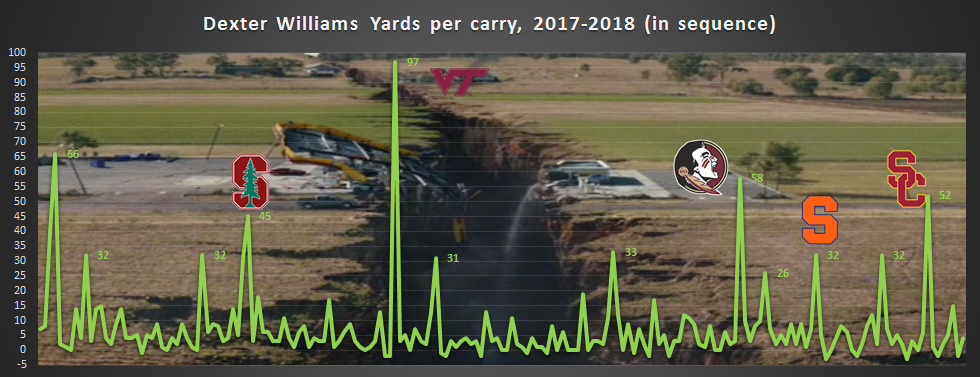

For the season Notre Dame finished 118th in run staff rate allowed, and 116th in opportunity rate, the percentage of carries where the offensive line produces at least five yards of room for the runner. The bright spot? Notre Dame finished 58th in marginal explosiveness, a statistic that increased dramatically when Dexter Williams returned against Stanford after an initial suspension. After the Virginia Tech game this year I compared Williams’ long runs to a seismograph – sooner or later, you knew a tremor was coming and then a full-on earthquake of a long run. I’ve updated the visual now through the end of the season, and raised the bar on my MS Paint and Powerpoint graphics skills:

Runs seem destined for inefficiency

The combination of Clemson’s penetrating run defense and Notre Dame’s inefficiency on offense doesn’t bode well for the Cotton Bowl. It’s probably the single biggest mismatch thinking about each run and pass attack versus either team’s defense. Not only will it be difficult to run efficiently, it’s also likely that many runs also won’t gain much if anything, landing Ian Book in obvious passing situations where Clemson’s pressure and pass rush can really be let loose.

Chip Long has been creative all season, and hopefully that innovation continues against a stellar defense. Notre Dame may benefit from a bit more of a pass-heavy attack than they’ve shown this season – despite Ian Book’s accuracy and efficiency, the run-pass balance has been nearly a 50/50 split in competitive time as a whole and on first downs. When the Irish do run, they should keep the Tigers off balance with misdirection and lots of runners to account for – some keepers for Book, jet sweeps with Chris Finke, and reads that can take at least one elite Tiger lineman out of a play.

The Irish should also be smart with the formations and personnel groupings they run out of – even in red zone and 3rd and short situations, utilizing multiple WR sets to spread out the Tiger front. It’s going to be difficult to open up run lanes against Venables group of mutants no matter what, but the difficulty only grows if heavy personnel packages allow the defense to put 9-10 guys in the box.

Irish Pass Offense vs. Clemson Pass Defense

A weaker piece of the Tiger defense….that’s still easily a top-10 unit

The Clemson pass defense enters the playoffs ranked 6th in Passing S&P+ defense, with many dominant performances but unlike the run defense, a couple of occasions where the Tigers were exploited. Still, the defensive line is still an issue (6th in adjusted sack rate), and opponents have been held to the 12th lowest pass efficiency and 16th lowest pass explosiveness.

The only weaknesses in their profile is that the Tigers have let up a few big passes – 5 of 50+ yards, and don’t get their hands on many passes, ranking just 92nd in pass breakups per game. Still, opponents are only completing 52.8% of their passes (9th nationally), so maybe the lack of deflections is due in part to lots of throwaways and passes way off because of the pressure Venables likes to bring.

The games that should give Irish fans hope against the nation’s top defense are Clemson’s matchups with Texas A&M in Week 2 and against South Carolina the final week of the regular season. Both teams were extremely pass heavy – A&M had 44 pass plays, averaging 9.7 yards per attempt (including sacks), and South Carolina’s Jake Bentley had 50 pass dropbacks and averaged 9.25 yards per pass play. Not coincidentally, those were two of the three best offenses per S&P+ the Tigers faced – the Aggies checking in at 19th, and Gamecocks at 29th.

Still, those performances have been the exception rather than the rule. In last week’s ACC Championship game, Pittsburgh actually had negative yards per pass play – the Panthers sack yardage lost exceeded the pass yardage gained! NC State, a passing attack S&P+respects (13th nationally), managed just 5.5 yards per attempt with no touchdowns and two picks.

A newfound strength for the ND offense – pass efficiency

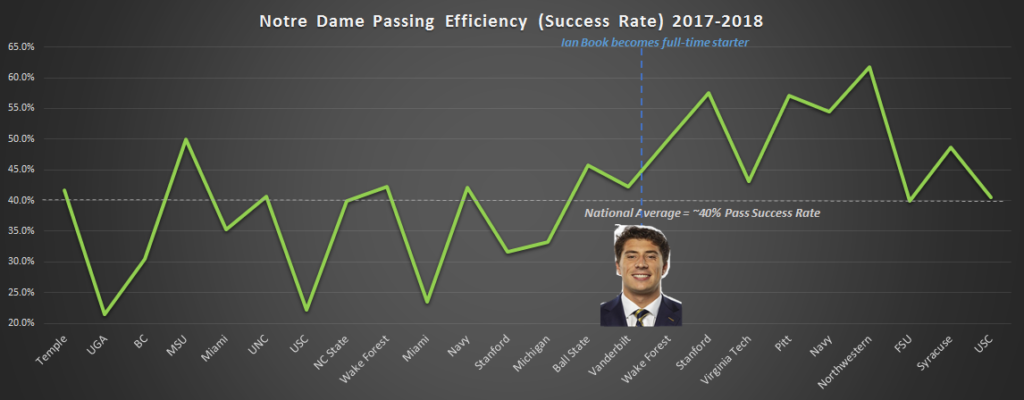

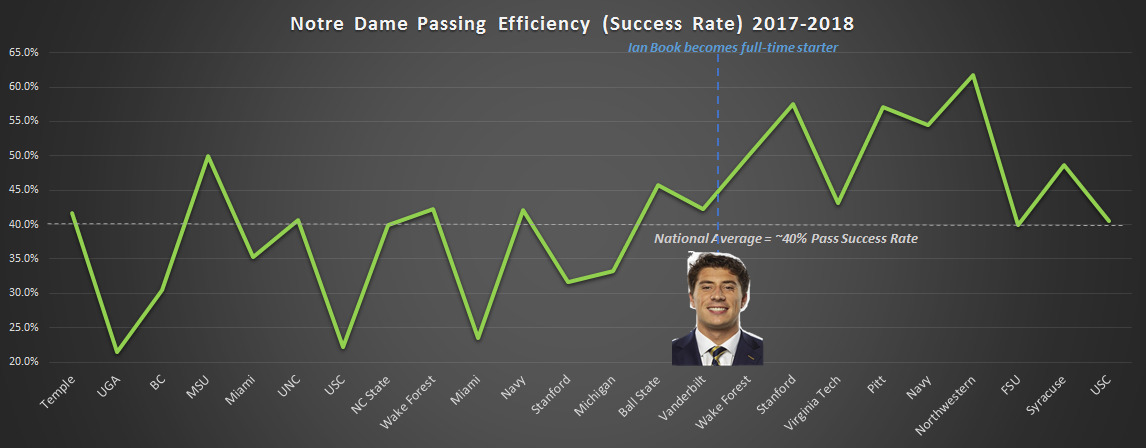

Entering the season, Irish fans were trying to piece together formulas for an effective offense with the assumption that the passing game would probably remain pretty inefficient. I’d be rich if I had a nickel for every offseason thread or debate I encountered speculating if Brandon Wimbush could raise his completion percentage to 55 or 58%. The surprise of the season was the emergence of Ian Book, and with it a hyper-efficient pass attack that changed the identity of the Notre Dame offense.

It’s a stark contrast looking at Notre Dame’s pass success rates over the past two seasons before and after Book’s ascent to QB1. Despite four games of average and in some games below average pass efficiency with Wimbush starting, the ND offense finished 21st in Passing S&P+ and 15th in marginal pass efficiency. Book’s generally quick decision and solid pass protection from Jeff Quinn’s crew also led to a strong finish limiting opponents sacks, finishing 33rd in adjusted sack rate, including 12th on passing downs.

The passing game hasn’t been quite as explosive, checking in at 54th in marginal pass explosiveness, and if Book has flashed any weakness it’s been deep accuracy. Chase Claypool and Miles Boykin have been reliable weapons with high efficiency and catch rates, but neither are burners downfield and the longest reception between them in 2018 is a 40-yard catch by Boykin. That wasn’t exactly a big downfield play either – it was the catch off a Book scramble at Virginia Tech where Boykin’s defender left him and the senior rumbled in from about 27 yards out after the catch for a score).

Expect Clemson to continue the strategy recent opponents have employed against Book – trying to confuse him with blitzers, dropping ends into coverage, and daring Book to connect with Notre Dame receivers downfield. Boykin, Claypool, Alize Mack, and Chris Finke will have to win contested balls in one-on-one situations, and probably break a big play or two.

Time to air it out

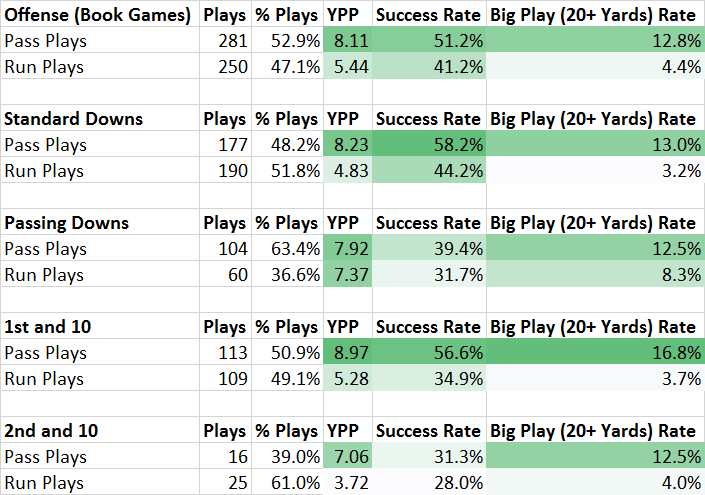

In addition to the Tigers having a slightly weaker pass defense, Notre Dame has been consistently better passing the ball than running since Book took over at Wake Forest. No matter which way you slice it – efficiency, explosiveness, situational stats – the pass game has clearly had an advantage. Despite this edge, after removing garbage time, the Irish have only passed it about 52% of the time versus 48% runs. On standard downs and 1st downs it’s a similar story – nearly 50/50. But should it be?

That’s some pretty strong evidence in favor of airing it out more – regardless of opponent – and with Clemson’s dominant run defense, all the more reason to chuck it around. Notre Dame fans may bristle at that idea – but there’s increasing evidence that a lot of the traditional arguments about running the ball aren’t backed up by data. At the NFL level at least, ideas like “you need to run to set up play action!” haven’t borne out, and I would expect the same to hold true at the college level (play-action is good and effective regardless of how often/well you run).

I think we should shift our mindset for this game. Two quotes…one you probably hear a lot, “The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result.” I take this a little further and say that if we KNOW something is probably not going to work, it’s insane to even attempt it. I dont think never calling a run play is the idea, but we need to think about how we can use the pass on a much higher basis in this game. Thankfully, we have the exact right QB to do it. Use Dex and Jafar as swing pass options, run more RPOs and highlight the P part of that equation.

Why? Because of the second quote, “There’s nothing balanced about 50 percent run, 50 percent pass, because that’s 50 percent stupid.” Thank you, Coach Mike Leach. We don’t need to force this mythical “balance” and have equal number of runs compared to passes. We need to win the game, not fall into some NDN wet dream while losing in miserable fashion. Get the balls to our playmakers in space and let them execute. If that means 75% pass to 25% run, let’s do it.

Amen.

The only stat that matters is your point differential relative to the other team. Have more points, however you get them. Dink and dunk and in the flat to the backs and take 15 plays to score with 14 of them being under 10-yard passes, I don’t care. Just win, baby.

I have always been amazed at how loud the calls on NDN are for the Bo Schembechler offense.

NDN, what’s that?

Naples Daily News. It’s weird that they care so much about Notre Dame football and know so much about Bo Schembechler, but I guess that’s Florida for ya

Florida and Germany, right?

Naples? I would have assumed Rome cared much more about ND’s season.

I’d be interested to see a game by game breakdown of run vs pass numbers since Book took over. It has seemed like in some of the games where we’ve stalled out on offense (VT comes to mind, and that big run against USC that set up the TD pass) that sticking with the run eventually paid off.

If I’m Long, I think I’d definitely start things off with an attack through the air (Book has been fantastic most games with quick out routes and screens, which will be needed against Clemson’s rush). But if Book can’t find his rhythm/the receivers can’t generate separation, I’d quickly shift back to the 50/50 run/pass formula.

At the end of the day, I don’t know how you beat this Clemson defense without some big time explosive plays, and Dex is our best big play threat. It’s going to be interesting to see what Long comes up with over the rest of this month.

I agree, and I think that’s where creativity is key. Throw in a draw play to Dex where maybe the DL gets too far upfield, or utilize Dex in the screen game or out of the backfield, or lined up wide then coming on a jet sweep. I think the runs we do have either need to be setting something up for later or ones we feel have a decent chance at confusing the defense and getting Dexter in space, because vanilla runs up the middle aren’t going to have much (if any space).

Here’s the game by game breakdown:

Wake Forest – 7.84 yards per run (68% success rate), 7.80 yards per pass (50% success rate)

Stanford – 5.76 yards per run (41.3% success rate), 7.73 yards per pass (57.6% success rate)

VT – 7.79 yards per run (37.5% success rate), 7.03 yards per pass (43.2% success rate)

Pitt – 3.74 yards per run (32.3% success rate), 6.63 yards per pass (57.1% success rate)

Navy – 6.62 yards per run (51.4%), 9.91 per pass (54.5%)

Northwestern – 3.07 yards per run (29.7%), 10.1 per pass (61.8%)

Syracuse – 3.16 per run (36%), 7.81 per pass (48.6%)

USC – 5.52 per run (36%), 8.12 per pass (40.5%)

So the pass game has been more efficient in 7 of 8 games, and averaged more YPP in 6 of 8 (and those were by less than a yard, compared to several games where the pass was several yards better than the run per play). I know there will be some thought of “you have to keep running and eventually break one” but at what cost? You can’t afford to fall behind this team, and there’s been games where we’ve kept running and haven’t broken one at all (Pitt or Northwestern).

I think a key hidden factor here is Book’s effectiveness on RPOs. Jamie at ISD mentioned this recently; for the season on RPOs Book is completing 88.9% at 9.02 ypa. A lot of that passing success is due to Book’s ability to make the right decision and execute RPOs at an absurdly high level. I’d be fine with doing plenty of that – I think that with Clemson’s aggressiveness on defense there are going to be some opportunities there in the RPO game.

I dont know how to quantify this, but I seem to feel that the errors Book makes on RPO are more on when he chooses to run it and makes the wrong running read. Like he’ll hand off with the DE crashing in or he’ll keep it when he should hand off. He almost always makes the right call to run or pass, though

So basically what I’m reading is that this win is going to go down in history as the “Tyler Newsome Game.”

Ugh. Of course, the Clemson staff knows these stats as well, so they’ll be looking for the air raid and daring us to run.

“So clearly I can’t choose the wine in front of me!”

the luxury Clemson has that some of our other opponents haven’t is that they have such a talented front seven that they may be able to stop the run without loading the box. I’ll definitely be looking early on to see 1) how often they’re bringing pressure vs just letting the DL work, 2) if we are able to find any run success when there’s even numbers in the box, 3) if they are dropping guys into zones to try to take away RPO passes (or give Book a run read). On the RPO’s I’d be crashing on the RB and trying to take away the quick pass, and if Book is beating you with his legs so be it and you can adjust.

You give me some hope. I guess from 10000 feet it’s easy to think, as I did above, “well, their front 7 is so good, they can just focus on stopping the pass and force ND to run into the teeth of it.” But as you (and Brendan above) point out, the devil is in really the details and the RPO game seems to open another dimension of the offense where ND maybe, possibly, hopefully, could find success. The RPO accuracy and ypa that Brendan points out is def pretty wild.

My mind is never quick enough to pick up the numbers in the box in real time (or even on replay most times) and my nights are never long enough to keep rewinding to check, but I agree that will be telling.

Thanks for the analysis!

To be clear, though, I’m always hopeful. It’s just way more fun than worrying about a team I don’t play for losing.

Definitely dont do Air Raid. Our team is absolutely not built for that. The QB, most certainly but also our receivers are not stretch-the-field guys. Boykin is big and powerful but slow and doesnt separate. Claypool is gadget-y but effective on the boundary only.

Agreed.

You’re actually giving me too much credit. I used Air Raid incorrectly because I guess don’t know what it really means. I just meant it as a cute way to say pass a lot.

Curious to see the affect of play-action in this game because Chip seems to really rely on that as a vehicle to keep the passing game productive. That’s one of those things where passing more isn’t going to help if Clemson isn’t respecting the run game anymore. We’d have to hope to hit 85 yards on 6 or 7 carries because the passing game efficiency will likely take a tumble.

Playing against great defenses is hard.

It is, but I guess the hope is that we can be the Ohio State to Clemson’s Michigan? Their defense looked like the best in the nation (with lots of DL talent, although not quite as much as Clemson) until all of a sudden it wasn’t in the wrong matchup

It depends if Clemson’s defense completely forgets how to defend a crossing route.

/ND calls all out and go routes

I did not enjoy reading this Michael. I did not enjoy it at all.

What’s the opposite of play action? Passing to set up the run and draws, misdirection, RB swings, and POPs? That’s what we need.

We really need the guys with super athleticism, like Claypool (of course someone with the initials CC is awesome), Mack, Kmet, and Armstrong to make plays.

I trust that Chip Long understands the challenge ahead of him and will do as much as can be done to gameplan it.

I think that awareness is key. And really to your comment and E’s above, I think the formula is sort of

1) pass early and often, because it offers significantly more hope of efficiency / explosiveness

2) hope that either by tendency shown or success that Clemson has to defend the pass more, resulting in more favorable run conditions. Sometimes run success is as easy as a numbers game with # of men in the box, and passing may clear that out a bit.

3) pray that we can win when we run in those situations, because I’m not sure that our OL can hold up even with 5 man boxes against this DL. otherwise it’s Leach time.

I also hope (and frankly, expect) they are spending a lot of bowl practice time on deep passes. I think Book’s accuracy and good decision-making in the RPO paired with effective downfield passing could mask a lot of the running game challenges. If we can’t stretch their defense out, it may be a long night.

Along those lines, most beat guys seemed to interpret BK’s recent comments about some freshmen maybe earning time in the playoff game that haven’t been a factor as most likely to be Lenzy and/or Keys, two of our fastest receivers. Not that Clemson won’t know what’s coming, but could see a few early posts or go routes a la freshman Golden Tate or ’12 Golson to Chris Brown in Norman.

My eye test tells me the same thing. The passing game is more effective. Do what works.

Chrome gold number trim with green gloves/cleats for the Cotton Bowl.

Hard to tell what to think of these without really seeing them, but that’s not what the internet is for.

I DO NOT LIKE

Honestly, I’ve always felt that metallic or chrome gold looks great on ND’s jerseys.

If you ignore the pants and helmets and focus only on the jersey top, I feel that the 2012 Shamrock Series jerseys are the best jerseys Adidas ever pumped out for ND. And we all loved the 2013 edition. More metallic gold, please

I hope they spend a lot of time working on pacing in their 15 practices. I think there will be a lot of value in getting to the line of scrimmage as quickly as possible, seeing how the defense sets up, and then either (1) getting the play off quickly if they like what they see or, otherwise, (2) stalling at that point to burn clock to shorten the game. I’m not sure if they’re at the point where they trust Book to run the offense like that, but it’d be huge if so.

What I really want to see is a liberal and creative use for Wimbush. A little wild cat here, a little 2 qbs in the backfield at the same time there, a little option between Book and Wimbush. Heck even a quick pitch to Wimbush with the option to throw. Keeping Clemson’s D guessing is going to be key in this game.

We will see a ton of this. The way to trick a team that is spending three weeks gameplanning to face Ian Book is to throw them Brandon Wimbush. Just as Book surprised LSU, Hurts surprised Georgia, Tua surprised Georgia, and Cardale Jones surprised everybody.